When we reach Gratiano in Othello, I can practically hear a student whisper, “Sir… isn’t he the loud guy from The Merchant of Venice?” Fair question. Shakespeare did enjoy recycling names.

But in Othello, Gratiano is a very different figure. He’s a minor character, yes, but like that quiet student who drops one sentence that changes the whole discussion, he matters. Appearing during the final catastrophe, Gratiano witnesses the wreckage, reacts with blunt honesty, and confirms the brutal reality of what remains.

His role is small, but strategic. His few lines anchor the ending with civic clarity, reminding us that Venice is watching, judging, and ultimately inheriting the consequences of private tragedy.

Who Is Gratiano in Othello?

Gratiano in Othello is Desdemona’s uncle and a Venetian noble who represents the city’s voice of order, law, and public conscience- showing up late in the play to witness the fallout and confirm the consequences. Unlike the soldiers and schemers around him, he stands for Venice itself: the courts, the council, and the cool reminder that private tragedy always circles back to public judgment.

Here’s how I explain it to my students in class: imagine Venice sending a spokesperson with stamped paperwork, not a sword. That’s Gratiano. He arrives in Cyprus with Lodovico carrying news that Brabantio has died “of grief,” and the line hits with the emotional dryness of an official report- painful, but procedural.

Gratiano doesn’t posture or duel. He observes, evaluates, and reacts with the blunt clarity of someone who has seen enough government meetings to know when things have gone horribly off-script.

During the final scene, when Iago’s web finally snaps, Gratiano becomes the civic microphone. His sharp line, “Torments will ope your lips,” lands like a court order rather than a threat. He’s not seeking revenge. He’s demanding answers on behalf of a city that deserves the truth.

And yes, as Desdemona’s last kin in Cyprus, he even inherits Othello’s estate- proof that Venice doesn’t just watch tragedy unfold, it files the paperwork afterward. So, who is Gratiano? Venice- walking, witnessing, and reminding us that chaos doesn’t erase accountability.

Table of Contents

Gratiano’s Character Traits in Othello

Gratiano shows up in Othello as a blunt, observant Venetian noble with a surprisingly sturdy moral spine, especially when the play collapses into chaos.

Now for the live classroom moment: I always tell my students, “Watch Gratiano’s mouth. He says what everyone else is thinking, but with less cushioning.” When he hears the “direful noise” in Act V, he instantly senses “some mischance,” which shows his observant nature.

But then comes his darker wit- after revealing Brabantio’s death, he adds he’s glad the old man didn’t live to see this disaster. Brutal? Yes. Honest? Also yes. That’s Gratiano’s insensitive bluntness at work.

Then the moral gear shifts. When Iago strikes Emilia, Gratiano explodes with outrage, demanding accountability: “Fie, fie upon thee, strumpet!” Suddenly, he’s not just watching. He’s condemning. By the end, he becomes the last surviving relative, quietly inheriting Othello’s estate, proof that in Shakespeare’s tragedies, even estates need a witness.

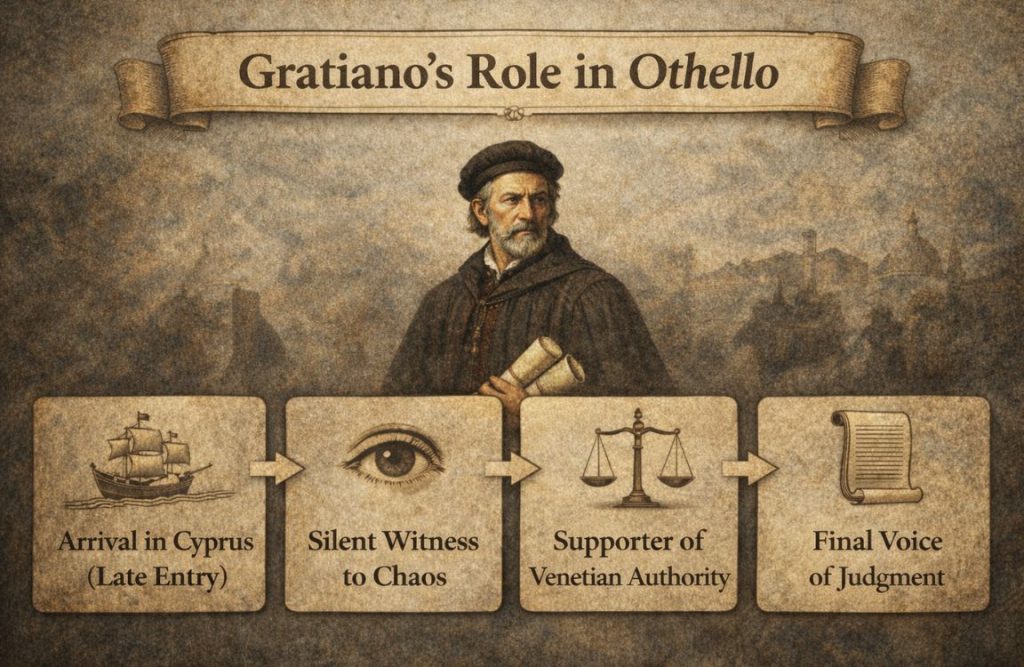

Gratiano’s Role in Othello

When students ask about Gratiano’s role in Othello, I tell them this: he doesn’t push the plot forward. He stands beside it, watching closely as it collapses. His role is subtle, deliberate, and deeply strategic.

i) His Arrival in Cyprus:

Gratiano enters Cyprus like a calm official stepping into a burning room. I imagine pausing my lesson here and saying, “Notice the timing.” He arrives after jealousy has already poisoned trust, and violence is no longer a threat but a fact.

His presence signals that the private disaster is about to face public eyes. Unlike earlier arrivals, Gratiano brings the weight of Venice with him- law, reputation, and consequence packed neatly into a few lines.

ii) His Role as a Witness, Not an Instigator:

In Othello, Gratiano watches, yes, watches, and that’s the point. Gratiano doesn’t scheme, provoke, or persuade. He observes. In a play crowded with manipulation, his stillness feels intentional.

He reacts to horror instead of creating it, becoming our stand-in as readers. Shakespeare uses him to show how shocking the tragedy looks when seen by someone untouched by Iago’s lies.

iii) How He Supports Lodovico and Venetian Authority:

In class, I call Gratiano the “backup voice of Venice.” He reinforces Lodovico’s authority not by arguing, but by agreeing- quietly, firmly, publicly. This matters.

Together, they represent order returning after chaos. Among the characters in Othello, Gratiano helps restore balance simply by standing on the side of judgment and law when emotions have run wild.

iv) Why Shakespeare Uses Him Late in the Play:

Shakespeare saves Gratiano for the end because clarity always arrives last. By placing him late, the playwright ensures that truth is seen without distortion.

Gratiano isn’t there to change events. He’s there to name them. And sometimes, that naming is the final, most powerful act.

What Does Gratiano Do in Othello in the Final Scene?

Gratiano steps into key moments in Act V, reacts to the shock of Desdemona’s death, and helps re-establish moral judgment after Iago’s schemes explode into daylight.

Now, picture my classroom at Act V, Scene 2. I ask, “What does Gratiano actually do here?” Students flip pages, expecting fireworks, but Gratiano works in quieter tools: facts, shock, and civic duty.

When he discovers Desdemona near death, his stunned “What is the matter?” feels like someone walking into a tragedy without warning. Moments later, he drops the crucial news that Brabantio is gone and won’t witness this horror- a detail delivered with dry, unsettling honesty.

As truth erupts, Emilia’s testimony, Iago’s exposure, Gratiano stands firm. He demands that Iago answer for “this dreadful deed,” and when chaos settles, he helps restore order, preparing to return with Lodovico to report Venice’s verdict on the wreckage left behind.

Analysis of Gratiano’s Character in Othello

When students ask me why Shakespeare even bothers with Gratiano, I smile. He looks minor, speaks little, and arrives late, but that’s exactly the trick. Gratiano is Shakespeare’s quiet instrument, tuned to moral awareness, realism, and tragic timing rather than dramatic fireworks.

i) Gratiano as a Moral Observer:

When I teach Gratiano, I describe him as the student sitting at the back of the class- silent, alert, absorbing everything. He rarely interferes, but when he speaks, his words matter.

As Desdemona’s uncle, he represents the Venetian moral world, watching events unfold with growing horror. His reaction to Desdemona’s death, “O murderous coxcomb!”, is not strategic or manipulative. It’s instinctive human outrage.

In that moment, Shakespeare gives us an unfiltered moral response. Gratiano doesn’t analyze evil like Iago. He recognizes it.

ii) Contrast Between Silence and Speech:

Here’s a live teaching moment I often pause on: Shakespeare makes noise meaningful by using silence. Gratiano’s long, quiet presence contrasts sharply with characters like Iago, who weaponize language nonstop.

Gratiano speaks rarely, but when he does, truth slips out naturally. His restraint highlights a key idea: speech in Othello is dangerous, but silence can be honest. Think of him as punctuation in the play: a sudden exclamation mark after too many deceptive sentences.

iii) Why His Late Appearance Strengthens the Tragedy:

Students often complain, “Sir, he comes too late!” Exactly. Gratiano arrives when the damage is already done, and that delay deepens the tragedy.

If he had entered earlier, reason might have interrupted chaos. His late arrival mirrors real life- help often comes after catastrophe. When Gratiano stands over Desdemona’s body, he becomes the audience’s stand-in, asking silently, How did it come to this? That helpless timing makes the ending hurt more.

iv) How Minor Characters Deepen Realism:

I tell my students this: tragedies don’t happen in empty rooms. Gratiano adds social texture- family ties, witnesses, consequences. Minor characters like him remind us that private crimes echo publicly.

Without figures like Gratiano, Othello would feel like a closed experiment. With him, it feels disturbingly real- like a tragedy that spills beyond the main characters and stains the world around them.

Gratiano in Othello Analysis Line by Line (Key Moments)

When I walk students through Gratiano’s lines, I do it slowly- almost with a magnifying glass. He doesn’t speak often, so each line carries weight. Take his shocked response after Desdemona’s death: “O murderous coxcomb!” I tell my class, pause here.

This isn’t poetic decoration. It’s raw, civic anger. The tone is blunt, public, and unmistakably Venetian- crime must be named, not whispered away.

Later, when Gratiano speaks of justice and punishment, his language turns formal and legal in spirit. He sounds less like a grieving relative and more like a representative of the Venetian order. That shift matters.

His words echo a society built on law, reputation, and accountability. Venice values control, clarity, and judgment, and Gratiano’s lines carry those values naturally.

Here’s the twist I love pointing out: Gratiano never argues emotionally like Othello or manipulates language like Iago. His tone stays grounded. Line by line, he reminds us that beyond passion and plots, a social code still exists- quietly waiting to speak when chaos has finished talking.

Themes Associated with Gratiano in Othello

When I teach themes through Gratiano, I tell my students this: he doesn’t carry themes loudly. He reveals them quietly. Like a mirror held at the edge of the stage, Gratiano reflects justice, truth, order, and judgment without ever stealing the spotlight.

i) Justice and Accountability:

One of Gratiano’s strongest thematic roles is his instinct for justice. When he reacts to Desdemona’s murder, his response is immediate and accusatory, not confused or self-pitying.

I often tell my class: Notice how he names the crime before asking why it happened. His language treats murder as a public offense, not a private mistake. That reflects Venetian values– actions demand consequences. Gratiano doesn’t debate guilt. He assumes accountability must follow. In a play full of excuses and emotional spirals, his certainty feels almost shocking.

ii) Silence vs Truth:

Here’s a classroom moment I enjoy: I ask students, Who speaks the most truth in Othello? Gratiano’s name rarely comes up- until we look closely. His long silence sharpens the truth of his few words.

Unlike Iago, who drowns truth in language, Gratiano lets truth surface naturally. His restraint suggests that truth doesn’t always need persuasion. Sometimes it just needs the right moment. In that sense, Gratiano proves silence can be honest, while excessive speech can be lethal.

iii) Order vs Chaos:

By the time Gratiano fully enters the action, chaos has already won. And that’s the point. He represents the structured world of Venice, arriving too late to stop emotional anarchy. His presence highlights the gap between social order and personal collapse.

I tell my students to imagine him as a clock chiming after the house has burned down- order still exists, but it can’t reverse damage. That tension sharpens the tragedy rather than softening it.

iv) Outsider Perspective on Othello’s Fall:

Gratiano watches Othello’s collapse without sharing his delusions or passions. That distance matters. As an outsider to Othello’s inner turmoil, Gratiano sees the fall clearly and reacts without emotional fog.

He reminds us how Othello’s private jealousy becomes a public disaster. Through Gratiano’s eyes, we see not a tragic hero reasoning badly, but a respected figure violating the moral code of his society- an act that cannot be undone.

Important Quotes by Gratiano in Othello

When revising Gratiano, I tell my students: don’t hunt for quantity. Hunt for precision. His few lines are like exam gold- short, sharp, and loaded with meaning. If you use them well, examiners notice immediately.

Quote 1: “Poor Desdemona! I am glad thy father’s dead.”

This line often shocks students, so I pause the class right here. Gratiano isn’t being cruel. He’s being brutally honest. The tone mixes pity with grim relief. He believes Brabantio would not survive seeing his daughter murdered by her husband.

In exams, use this quote to show Gratiano’s plain-speaking nature and his moral clarity. Examiners like answers that explain why the line sounds harsh and what it reveals about Venetian attitudes toward honor and family shame.

Quote 2: “Thy match was mortal to him.”

Here, Gratiano links Desdemona’s marriage directly to her father’s death. I tell my students to treat this line like a verdict. The implication is social, not emotional- crossing norms has consequences.

This quote works beautifully in exams to connect private choices with public damage. It also helps you show how Gratiano voices society’s judgment rather than personal emotion, a key contrast examiners appreciate.

Quote 3: “All that is spoke is marred.”

This line sounds simple, but I always warn students: don’t underestimate it. Gratiano suggests that words arrive too late to repair the damage.

In exams, use this quote to comment on delayed truth and irreversible loss. Examiners reward students who link this line to the tragic finality of the play, rather than summarizing events.

Gratiano in Othello Summary (Plot Contribution)

When students want a quick recap, I frame Gratiano as the late-arriving witness. He enters in Act V, not to stir the plot but to seal it. His arrival coincides with Desdemona’s death, and from that moment, the play’s private tragedy becomes public knowledge.

After Gratiano appears, secrecy collapses. Accusations replace suspicions, and the room fills with witnesses rather than whispers. His reactions- brief, direct, unembellished- signal that events can no longer be hidden behind emotion or rhetoric.

In the final resolution, Gratiano helps shift the play from chaos to judgment. He doesn’t fix the tragedy, but he confirms it. Like a court record written after the crime, his presence ensures that what happened will be named, remembered, and answered for.

Does Gratiano Die in Othello?

No, Gratiano does not die in Othello. I always pause here in class and ask, “Who survives to witness the aftermath?” His survival is more than luck. It’s Shakespeare’s way of keeping a moral lens intact.

Gratiano lives to speak truth, mark justice, and reflect Venice’s social order. While Othello, Desdemona, and Iago fall into chaos, Gratiano’s continued presence reminds us that not all order is destroyed. He becomes the play’s moral witness, quietly testifying that even in tragedy, honesty and societal conscience endure.

How Many Lines Does Gratiano Have in Othello?

Gratiano speaks roughly 20 lines in the entire play- most of them packed into the emotional whirlwind of Act V.

Now here’s the teaching twist: I love showing my students that Shakespeare doesn’t measure importance by line count. Gratiano barely talks, yet he steps in at the end like a city clerk closing a disaster report.

In the final scene, after the truth about Iago detonates and the stage is covered in consequences, Gratiano drops the quietly devastating, “All that’s spoke is marr’d.” It’s a reminder that sometimes the smallest voices carry the most civic weight- proof that impact isn’t about volume, it’s about timing.

Gratiano vs Other Minor Characters in Othello

Compared to other minor figures, Gratiano is the steady civic witness, Lodovico is Venice’s official messenger, and Montano is Cyprus’s soldierly order, together forming the triangle of authority that survives the tragedy.

Now here’s how I explain it in class. I ask, “If Venice sent a committee to check on Cyprus, who’s doing what?” Suddenly, the comparison clicks. Lodovico and Gratiano in Othello arrive from Venice with news, documents, and a faint smell of bureaucracy. Lodovico delivers commands from the Senate, reads letters, and ultimately pronounces sentences. Gratiano stands beside him, watching the fallout with sober eyes.

Meanwhile, Montano in Othello embodies Cyprus itself- military stability with a splash of local dignity. He’s wounded in the drunken brawl, sidelined by chaos, and becomes living proof that Iago’s poison reaches institutions, not just lovers.

So who speaks for Venice? Lodovico.

Who witnesses injustice up close? Gratiano.

Who represents order on the island? Montano.

And when the bodies fall and the truth surfaces, guess who’s still standing? The committee.

Venetian Authority in Othello: Gratiano, Lodovico, and Montano Compared

| Character | Represents | Key Function | Symbolic Role |

| Gratiano | Venice (civic witness) | Observes tragedy & confirms aftermath | Voice of public conscience |

| Lodovico | Venice (official authority) | Delivers commands & sentences | State justice |

| Montano | Cyprus (local order) | Maintains military stability | Institutional order |

Why Gratiano Matters in Othello (Final Thoughts)

Gratiano matters because he becomes Shakespeare’s quiet judge- proving that even minor figures can shape how we understand major tragedies.

Here’s how I wrap it up in class: when we talk about Gratiano in Othello, students often shrug at first (“He barely talks, sir!”). And that’s exactly the point. Shakespeare loves handing the final moral clipboard to the quiet ones. Gratiano doesn’t duel, scheme, or monologue. He watches, names what he sees, and forces the audience to reckon with it.

In a play where passion erupts like a volcano, he’s the civil servant who shows up afterward to assess the damage.

In other words, great tragedies aren’t just built by heroes and villains. Minor characters seal the meaning. And Gratiano is the one who reminds us that Venice will record, judge, and remember what happened, even after the curtain falls.