When I introduce Othello in class, I can almost see the question forming in my students’ eyes: What is the Moor in Othello, and why does Shakespeare keep repeating it? Here’s my teacher’s answer. Othello is called “the Moor,” not to name his job or title, but to mark his identity.

In Othello, the word ‘Moor’ signals race, culture, and difference all at once, as a label slapped onto a person before we even hear his voice.

Shakespeare chooses this word carefully. Sometimes it sounds respectful, even grand. Other times, in Iago’s mouth, it sharpens into a weapon. That tension, between honor and prejudice, is where the tragedy begins.

Listen closely, I tell my students: the word “Moor” doesn’t just describe Othello. It quietly pushes him toward conflict, self-doubt, and downfall.

Table of Contents

What Does “Moor” Mean in Othello?

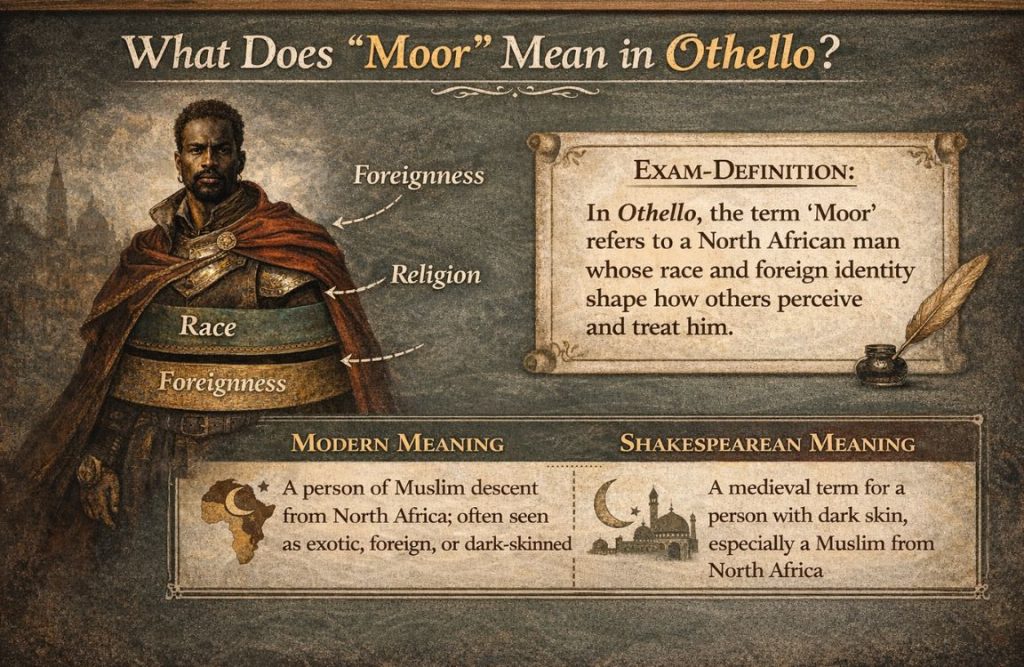

The meaning of Moor in Othello is not as simple as pointing to a dictionary. When I explain this in class, I tell my students to imagine a word wearing many coats at once- race, religion, and foreignness layered together. Shakespeare’s “Moor” shifts meaning depending on who is speaking and why.

i) Definition of Moor in Othello:

Let me put this in classroom English, no Shakespearean fog, no academic smoke. To define Moor in Othello, I tell my students this: a “Moor” is a dark-skinned man from outside Europe, often associated with Africa and Islam, seen by Elizabethans as culturally and racially different.

Now here’s your exam-ready sentence– underline it, star it, love it:

In Othello, the term “Moor” refers to a North African man whose race and foreign identity shape how others perceive and treat him.

Here’s the twist I enjoy pointing out on the board. Today, the word “Moor” feels outdated and uncomfortable, like an old coat that no longer fits modern language. But in Shakespeare’s time, it wasn’t a precise racial label. It was a broad, blurry term.

When characters from Othello say things like “an old black ram” or sneer at “the thick-lips”, the word “Moor” quietly gathers these insults around it- absorbing prejudice without always shouting it aloud.

That’s why the term matters so much. It’s not just what “Moor” means, but what people load into it.

ii) Moor Meaning in Shakespeare’s Time:

Here’s where history walks into the classroom and pulls up a chair. To understand Shakespeare’s moor, we need to forget modern categories for a moment. In the early modern world, a “Moor” could mean someone from North Africa, a Muslim, or simply a dark-skinned foreigner. Geography, religion, and race were tangled together like headphones in a pocket.

When students ask me, what is a Moor in Shakespeare, I answer: it’s a flexible label, not a fixed identity. Shakespeare uses that flexibility on purpose. The word can sound dignified in one breath and threatening in the next: “I hate the Moor” lands differently when you know how elastic the term was.

That looseness gives the word power. It allows fear, curiosity, and admiration to exist at the same time. And that uneasy mix? That’s the emotional fuel Shakespeare pours straight into the tragedy.

Who Is the Moor in Othello?

When a student asks me this, I don’t hesitate. I tap the book and say, look closely. Shakespeare tells us right away. The “Moor” is not a mysterious figure lurking in the background. He walks straight into the play wearing authority, experience, and contradiction.

i) Was Othello a Moor?

Yes, clearly and unmistakably, Othello was a Moor. I remind my class that Shakespeare doesn’t hide this. He frames it. Othello is a seasoned military general, trusted to defend Venice itself. That’s no small job. You don’t hand your city’s safety to someone you don’t respect. When the Duke declares, “Valiant Othello, we must straight employ you,” it’s a public stamp of approval.

Here’s the teaching twist I love. Venice accepts Othello not because it is suddenly free of prejudice, but because he is useful, capable, and victorious. His sword earns him a seat at the table. In uniform, he is celebrated. Out of it, he is questioned.

I tell my students to notice how admiration and unease coexist- like applause with a wince underneath. Othello’s identity never disappears; it just gets politely ignored until someone like Iago drags it back into the spotlight.

ii) Othello, the Moor of Venice:

Now let’s talk about that loaded title: the Moor of Venice. On the surface, it sounds almost ceremonial, like a medal pinned to his chest. But listen carefully. It doesn’t say Othello of Venice. It says Othello, the Moor of Venice. That phrasing matters.

In class, I compare it to being forever introduced with a qualifier you can’t shake. Othello is Venice’s hero, yes, but he remains slightly outside its walls. He commands armies, yet never fully belongs.

When the play calls him the Moor of Venice, Shakespeare balances honor and distance in one breath. The city claims his service, not his identity. That tension, between celebrated defender and racial outsider, is the fault line the tragedy quietly builds upon.

What Race Is Othello?

This is the moment in class when hands go up, voices overlap, and someone finally blurts out, “Sir, but what race is Othello?” I smile—because Shakespeare wants us right here, slightly uncomfortable and deeply curious.

i) Othello’s Ethnicity and Background:

When we talk about Othello’s ethnicity, I ask my students to resist the modern urge to label too quickly. Shakespeare gives us clues, not a passport. Othello is described as coming from beyond Europe, with strong links to Africa, most likely North Africa.

He speaks of vast deserts, royal courts, and a life shaped by travel and warfare. All signs point toward an African origin, but Shakespeare never pins a neat label on him.

That ambiguity is deliberate. In my classroom, I compare it to a silhouette behind a curtain: you see the outline clearly, but the details stay blurred. Othello’s race matters not because of biology alone, but because of culture. He is foreign to customs, stories, and history.

His “otherness” isn’t just in how he looks. It’s in how he speaks, remembers, and loves. Shakespeare keeps his background fluid so that prejudice can flow freely into it. The audience fills in the gaps, often with fear or fascination. And that, I tell my students, is exactly the point.

ii) Was Othello Black?

Now we reach the line that always makes students lean forward: “Haply, for I am black.” Othello says it himself. That single phrase carries enormous weight. For Elizabethan audiences, “black” did not function as a precise racial category the way it does today. It blended skin color with moral anxiety, foreignness, and even superstition.

I remind my class that when Shakespeare’s audience heard “black,” they often thought in contrasts- light versus dark, familiar versus strange. Othello’s words show us that he has absorbed these ideas. He doesn’t just hear society’s judgments. He internalizes them.

That moment is tragic not because of what others say about him, but because he begins to believe it. And that belief- quiet, corrosive, and unchallenged- is far more dangerous than any insult spoken aloud.

Moor in Shakespeare and Elizabethan England

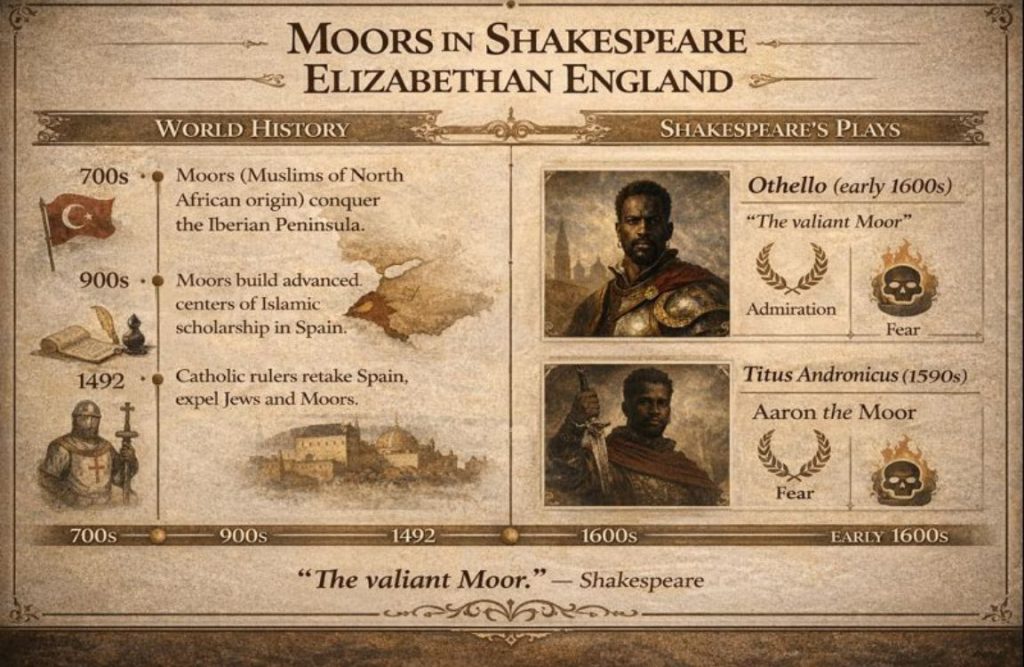

This is where I tell my students, step back from the play for a moment. History is about to walk onstage. Shakespeare didn’t invent the idea of the Moor. He inherited it, reshaped it, and turned it into drama.

i) Moors in Shakespeare’s Plays:

When we scan Shakespeare’s works, one thing becomes clear: among all the Moors in Shakespeare, Othello stands alone. Others appear briefly, often as references or stereotypes, but Othello is fully alive. He speaks in long, confident speeches. He loves deeply. He commands armies. That alone makes him Shakespeare’s most complex Shakespearean Moor.

In class, I like to point out the contrast. In Titus Andronicus, Aaron the Moor is painted in sharp, villainous strokes. He boasts of evil and delights in chaos. Othello, by comparison, enters as a noble hero.

When characters call him “the valiant Moor”, the word carries admiration. Shakespeare is clearly experimenting- asking how far he can stretch a familiar figure beyond expectation. Othello is not a symbol passing through the play. He is its emotional engine. And that makes his fall far more unsettling than any stock villain’s defeat.

ii) Moors and World History:

To really grasp this, I invite my students to time-travel. The Moor’s definition in world history points us toward North Africa and the Iberian Peninsula, regions shaped by Islamic rule, scholarship, and military power. Medieval Europe both admired and feared the Moors- for their learning, their armies, and their difference.

By Shakespeare’s time, that history had turned into myth and anxiety. The moor’s meaning in Shakespeare draws on this shared memory of foreign strength and cultural distance. Moors were imagined as travelers from another world- exotic, capable, and unsettling. Elizabethan audiences brought those assumptions with them into the theatre, like invisible luggage.

Shakespeare didn’t unpack it for them. He let it sit there, heavy and uncomfortable. And that weight presses down on Othello, shaping how every word, glance, and accusation is understood.

Is the Term “Moor” Offensive in Othello?

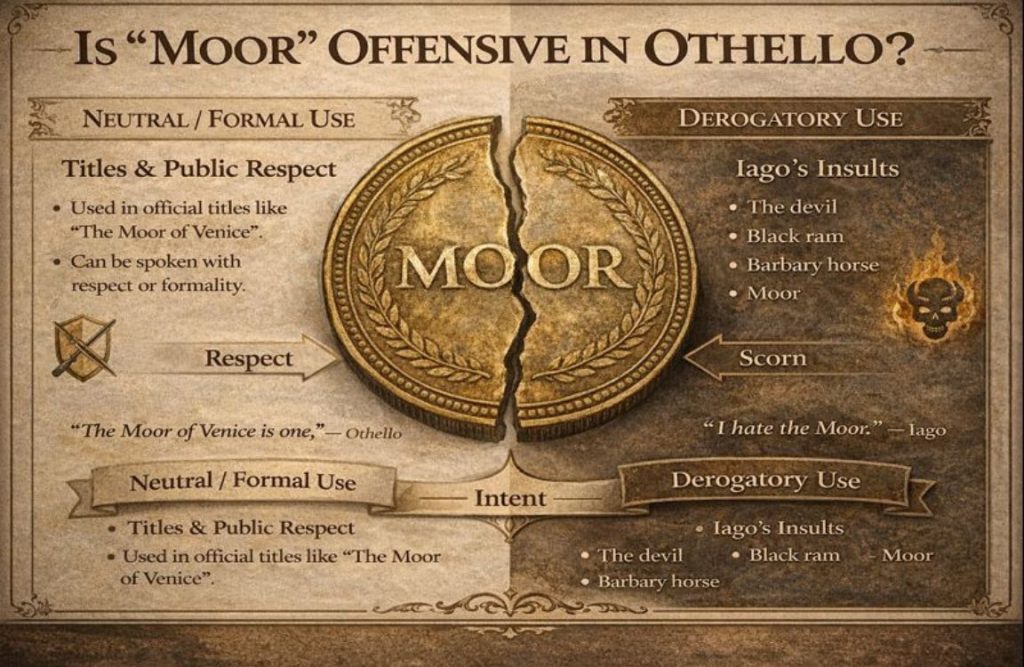

This is the question that makes my classroom go quiet. Students sense the tension in it. And rightly so, because the answer depends less on the word itself and more on the mouth it comes from.

i) Is “Moor” a Neutral or Derogatory Term?

When I explain the term ‘Moor’ in Othello, I tell my students to imagine a coin. Flip it one way, and it shines. Flip it the other way, and it cuts. The word “Moor” can function as a formal identifier, almost a title, especially in public settings.

In official moments, it sounds neutral, even respectful. It names Othello’s difference without attacking it.

But then Shakespeare lets the word loose in private conversations, and everything changes. This is where students begin to see why asking “Is Moor derogatory in Othello?” isn’t a simple yes-or-no question.

Characters like Iago use the word strategically. He repeats it instead of Othello’s name, stripping away individuality. When someone says, “I hate the Moor,” the word stops being descriptive and becomes dismissive.

In Othello, the use of the word ‘Moor’, depends entirely on intent. Some speakers acknowledge Othello’s status. Others reduce him to a label. I like to tell my students that Shakespeare turns the word into a mirror. It reflects the speaker’s prejudice more than Othello’s identity. The insult isn’t hidden in the syllables. It lives in the motive behind them.

ii) Racism and Language in Othello:

Now we step into darker territory, racism in Othello, not as a theme shouted from the stage, but as a poison whispered into ears. Iago rarely argues openly. Instead, he paints pictures. His language is packed with animal imagery and racial suggestion, images that stick to the mind. Once planted, they grow.

This is how race in Othello works. Words don’t just describe reality. They reshape it. The audience hears Othello through Iago’s metaphors before they fully hear Othello himself. That imbalance matters. Shakespeare shows us how racial issues in Othello are sustained not by laws or armies, but by repetition, by saying the same loaded ideas until they feel true.

When I pause the class here, I remind them: the most dangerous racism in the play isn’t loud. It’s persuasive. And that’s why Shakespeare’s language still unsettles us centuries later.

Why Shakespeare Emphasizes “The Moor”

At this point in the lesson, I close the book and ask my students to listen to what’s missing. Not what’s said, but what’s withheld. Shakespeare keeps returning to one phrase for a reason.

i) The Moor as a Symbol of Otherness:

When Othello loses his name, he loses a layer of himself. While teaching the Moor in Othello, I point out to my students that the shift from “Othello” to “the Moor” is subtle but devastating. A name anchors us. A label floats. Once characters stop naming him, they stop seeing him fully. He becomes an idea instead of a person.

Shakespeare’s Moor stands permanently at the edge of the circle, invited in, but never quite at home. That outsider status hums beneath every scene. Even moments of praise carry distance, like compliments delivered through a window.

When I explain Shakespeare’s Moor, I compare him to a guest who is welcomed warmly but never given a key. The tragedy feeds on that exclusion the way fire feeds on oxygen. The more Othello is defined by what he is not, the easier it becomes for suspicion and doubt to stick to him.

ii) Power, Identity, and Tragedy:

Here’s the part that always hits my students hardest. Othello doesn’t just hear society’s whispers. He starts repeating them to himself. That’s where power shifts.

When I discuss Othello’s Moor, I describe internalized racism as a crack in the armor, the general who once stood tall begins to bend inward.

Lines like “Haply, for I am black” show how Othello’s background becomes a lens through which he judges his own worth. His confidence drains, and jealousy rushes in to fill the space. The tragedy doesn’t erupt from the outside. It germinates quietly within.

Shakespeare shows us how identity, once shaken, can turn strength into vulnerability. And that transformation- quiet, psychological, irreversible- is what makes Othello so painfully human.

Key Quotes About the Moor in Othello

When revision season hits, I tell my students this: Shakespeare hides whole arguments inside single lines. These are the quotes about the Moor in Othello that examiners love, and for good reason.

i) “I hate the Moor” (Iago)

This line is brutally simple, which is exactly why it works. There’s no metaphor, no poetry, just raw hostility. When I pause on “I hate the Moor” in class, I remind students that hate this direct doesn’t need justification.

The speaker, Iago, refuses explanation. The word “Moor” replaces a name, reducing Othello to a target rather than a person. In exams, this quote is perfect for showing how prejudice can be blunt, unapologetic, and dangerously efficient.

ii) “An old black ram is tupping your white ewe” (Iago)

Students never forget this one, and Shakespeare knows it. The image is shocking, animalistic, and deliberately vulgar. When we unpack “old black ram”, I explain how the language strips Othello of humanity and turns fear into spectacle.

The contrast between “black” and “white” is designed to provoke disgust. It’s racism working through imagery, not argument, bypassing reason and going straight for emotion.

iii) “Haply, for I am black” (Othello)

This line hurts in a quieter way. Othello isn’t being insulted here. He’s doing the work himself. When I read it aloud, the room always stills. He absorbs the judgments around him and turns them inward.

That moment shows how repeated prejudice reshapes self-worth. In exams, this quote shines when analyzing how identity, once questioned, can become a weapon turned inward.

iv) “If she be black, and thereto have a wit, / She’ll find a white that shall her blackness fit.” (Iago)

When I pause on this line in class, I watch students wince, and good. Iago turns color into currency, trading in poison disguised as wit. I tell my students: this isn’t about Desdemona at all. It’s about how the idea of the Moor infects language, bending “blackness” into moral dirt. Racism here wears a clever grin.

v) “The Moor is of a free and open nature.” (Iago)

This is the line where I tap the desk and say, “Listen carefully, this is how predators speak.” Iago sounds almost complimentary, but it’s a trap wrapped in praise.

I tell my students: the word “Moor” replaces Othello’s name, turning trust into a weakness. Like leaving your front door open, goodness becomes exploitable, and tragedy walks right in.

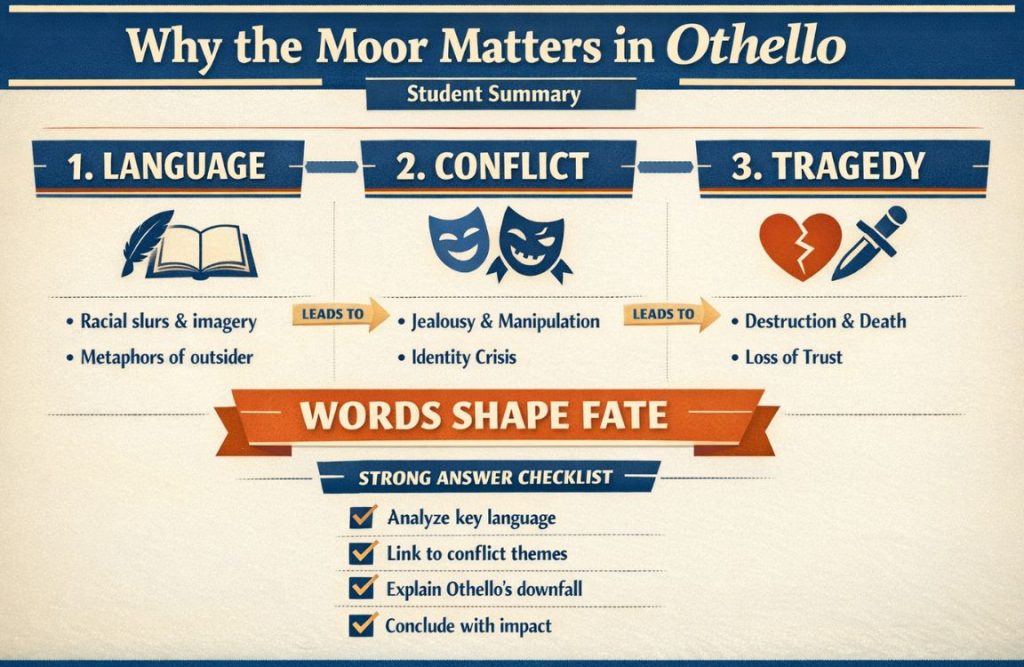

Why the Moor Matters in Othello?

When I wrap up this lesson, I tell my students: In Othello, if you understand the meaning of Moor, you understand the play’s heartbeat. Examiners love this term because it opens doors- to identity, power, jealousy, and tragedy- all at once. When asked who is the Moor in Othello, don’t just name the character. Explain why the label matters.

A strong answer does three things. First, it shows awareness of language. Notice how the word “Moor” replaces Othello’s name and shapes how others see him. Second, it connects language to conflict. Lines like “I hate the Moor” and “Haply, for I am black” prove that words don’t sit quietly on the page. They push the plot forward.

Finally, it links the term to tragedy. I often say this in class: Shakespeare doesn’t destroy Othello with swords or storms, but with a word repeated until it sticks.

Write with clarity, quote briefly, and always explain the effect. That’s how you turn understanding into marks.

FAQs:

Does Desdemona call Othello a Moor?

No, and that absence matters. Desdemona speaks to Othello with affection and respect. She calls him by name, not by label. When others say “the Moor,” it creates distance. Desdemona refuses that distance, and Shakespeare wants us to notice.

Is “Moor” an insult in Othello?

It can be. In formal settings, it sounds neutral. In hostile mouths, “I hate the Moor” it sharpens into an insult. Context is everything.

Why did Shakespeare make Othello a Moor?

To place him at the crossroads of admiration and suspicion. Being different makes him visible, vulnerable, and tragically isolated.

Who is the jealous Moor in Othello?

Othello himself. His jealousy doesn’t appear overnight. It grows slowly, fed by doubt and whispered suggestion.

What are the five Moorish principles?

That’s a trick question. Shakespeare gives us no such list. If you see it in an exam- smile, skip it, and keep writing.

Conclusion:

As I tell my students when we close the book, the Moor in Othello is never just a label. It is the engine of the tragedy. That single word carries identity, power, fear, admiration, and prejudice all at once.

Shakespeare uses it to show how language can lift a man up and quietly pull him apart. Othello begins as a respected leader, but the repeated emphasis on his difference slowly reshapes how others see him, and how he sees himself.

If you listen closely, the word “Moor” echoes through every conflict, every doubt, every tragic choice. Understand that, and you’re no longer just reading Othello. You’re hearing how words shape fate, one dangerous syllable at a time.