When I teach Othello, I always pause and ask my students a simple question: What if we watched this tragedy through the women’s eyes? Suddenly, the play shifts. Women in Othello are not decorative figures on the margins. They are the emotional fault lines along which the tragedy cracks open.

The representation of women in Othello reveals how love, loyalty, and silence are shaped and punished by a rigid patriarchal world. Desdemona loves boldly and pays dearly. Emilia speaks late but truthfully. Bianca is judged before she is heard.

As I tell my class, Shakespeare doesn’t just show us jealousy in Othello. He shows us how sexism feeds it. Or, as Emilia sharpens it: “They are all but stomachs, and we all but food.” That line still stings, because it’s meant to.

Role of Women in Othello: Meaning & Overview

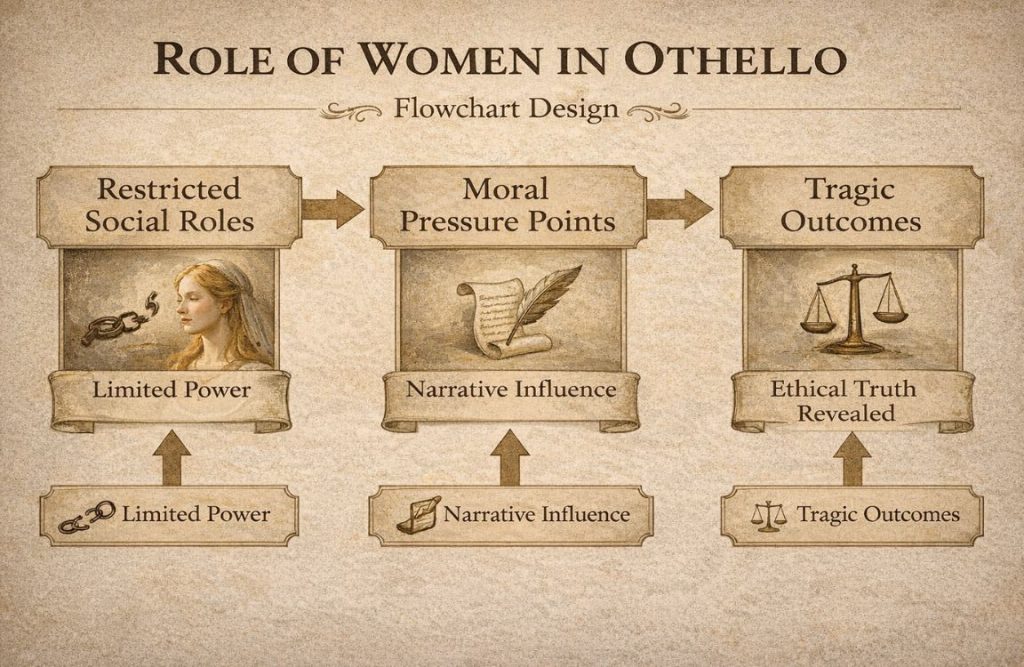

In short, women in Othello function as moral and narrative pressure points in a patriarchal world, where their restricted roles expose male insecurity and drive the tragedy forward. Simply put, although socially powerless, women shape the plot, reveal ethical truth, and determine the play’s tragic outcome.

When my students ask, “Sir, what exactly is the women’s role in Othello?” I smile because that question opens the whole play like a trapdoor. At first glance, women seem confined to predictable boxes: daughters, wives, dependents. But look closer, and you’ll see they are the quiet engines driving the tragedy forward.

In Othello, women exist in a tightly controlled social world. As daughters, they are expected to obey their fathers without question. Brabantio’s shock at Desdemona’s marriage isn’t just personal. It’s cultural. As wives, women are meant to be loyal, silent, and pure.

Think of Desdemona: admired when obedient, condemned when suspected. And socially, women depend on men for status, protection, and voice. Independence is not just discouraged. It’s dangerous.

Here’s where I pause in class and say, “Notice something odd?” Although women hold little formal power, the plot collapses without them.

- Desdemona’s secret marriage ignites the conflict.

- Emilia’s stolen handkerchief fuels Iago’s lies.

- Bianca’s treatment exposes society’s double standards.

Shakespeare uses women like pressure points- small actions, enormous consequences.

What fascinates me most is how their limited roles magnify male insecurity. Othello’s tragedy doesn’t begin with war or politics. It begins with fear about a wife’s loyalty.

As I tell my students, this play runs less on swords and more on suspicion. Or, as Emilia bluntly puts it, “Let husbands know their wives have sense like them.” That single line cracks the illusion that women are passive or simple.

So, the women’s role in Othello is not decorative. It’s structural. They may be socially restrained, but narratively, they are indispensable. Shakespeare shows us a world where women are controlled by men, yet the fate of men depends entirely on how they treat them. That irony? That’s where the tragedy truly lives.

Gender Roles and Patriarchy in Othello

Whenever I introduce this topic in class, I tell my students to imagine Othello as a house built by men, for men, where women are allowed to live, but never to redesign the rooms. That imbalance fuels much of the sexism in Othello and quietly steers the tragedy.

i) Elizabethan Views on Women and Marriage:

To understand the gender roles in Othello, we have to step into the Elizabethan mindset- a world where obedience was considered a woman’s highest virtue. A “good” woman was expected to be chaste, silent, and compliant.

Think of it as a three-part moral dress code: behave, obey, and don’t ask questions. Marriage, then, wasn’t a romantic partnership. It was a social contract. Love was optional. Control was not.

In this context, the treatment of women in Othello begins to make grim sense. A woman moved from her father’s authority to her husband’s, as a legal document passed between hands. Speaking too freely, or loving too boldly, was seen as rebellion.

I often pause here and tell my students, “Notice how dangerous female independence looks in this play.” It’s not that women lack intelligence or emotion. It’s that society refuses to make room for them.

Shakespeare writes women into a world that doesn’t quite want to hear them, and then lets the consequences echo.

ii) Women as Property and Social Dependents:

Nothing exposes women as possessions in Othello more clearly than Brabantio’s reaction to Desdemona’s marriage. He doesn’t say, “My daughter is unhappy.” He cries theft.

As if Desdemona were a stolen jewel, not a thinking, choosing human being. This is the patriarchal logic of Othello at its most revealing: marriage framed as ownership.

I tell my students to underline the language of possession, “my daughter,” “my jewel,” “my property.” Marriage becomes a transfer of goods, not a meeting of minds. Women rely on men for protection, status, and even credibility. Without male endorsement, they are socially weightless.

Shakespeare shows us a system where women are treated as dependents, and then asks us to watch what happens when men value control more than trust. The tragedy answers that question brutally.

Female Characters in Othello: A Comparative Study

When I line up the female characters in Othello for my students, I tell them we’re not ranking personalities. We’re tracing pressure points. Each woman reveals something sharp about power, love, and the fragile relationships between men and women in Othello.

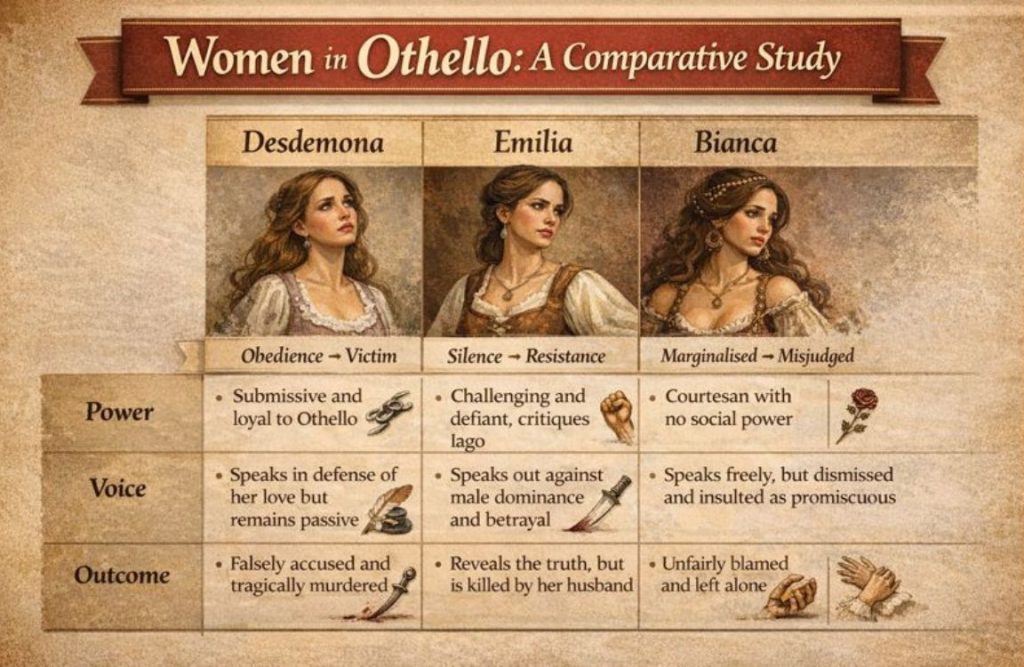

i) Desdemona: The Ideal Wife and Tragic Victim

Desdemona often enters the classroom wrapped in adjectives my students know by heart: loyal, gentle, innocent. And yes, she is all three. But I ask them to listen to how she is loyal. She loves without bargaining, trusts without receipts, and believes goodness will protect her.

In Shakespeare’s world, that faith becomes dangerous. This is the cruel brilliance of the female experience in Othello: virtue does not equal safety.

Watch Desdemona’s silence. It’s not emptiness. It’s obedience trained into a habit. When accused, she doesn’t shout her innocence. She waits for love to recognize her. That wait costs her everything.

I pause the class here and say, “Notice who gets to explain and who gets explained away.” Othello speaks. Desdemona listens. And listening, in this play, is lethal.

Her tragedy lies not in wrongdoing but in being misread. The female experience in Othello turns affection into evidence and purity into suspicion.

Even at the end, Desdemona protects the man who destroys her: “Nobody; I myself.” Every time we read that line, the room goes quiet. It’s the sound of ideal love colliding with unchecked jealousy and losing.

ii) Emilia: The Voice of Resistance

Every year, there’s a moment in my classroom when Emilia finally wakes everyone up. Desdemona may break our hearts, but Emilia sharpens our minds.

If Desdemona shows us what obedience costs, Emilia shows us what honesty risks. She lives inside the world of male attitudes towards women in Othello, but unlike others, she refuses to decorate that world with silence.

Her great speech, “Let husbands know / Their wives have sense like them,” is one of the boldest feminist quotes in Othello, and I always pause after reading it aloud.

Emilia doesn’t whisper rebellion. She states it like a fact of nature. Men cheat, lie, and desire freely, she argues- so why must women carry all the blame? In that moment, Shakespeare lets a woman say what society would rather suppress: inequality isn’t moral truth. It’s a habit.

What fascinates me is Emilia’s timing. She speaks after years of obedience, not instead of it. That makes her courage heavier, not lighter. When the truth finally matters most, Emilia chooses integrity over safety, truth over marriage.

I tell my students, “This is the most dangerous decision in the play.” And it is. Emilia’s resistance costs her life, but it exposes the rot beneath male authority.

In a tragedy crowded with loud men, Emilia’s voice arrives late, but it lands like a verdict.

iii) Bianca: The Marginalised Outsider

Bianca is the character I use to teach my students that not all marginalisation in Othello is subtle. She is what I call a living footnote: present, noticed, but dismissed.

As one of the women as outsiders in Othello, she suffers not only from her class but from the sexual double standards that color every interaction. Men’s desires and suspicions define her existence- her worth measured less by character than by the handkerchief she carries or the jealousy she incites.

I always pause when reading her scenes aloud and ask, “Notice how she reacts to attention versus how the men perceive her?” It sparks immediate debate. Bianca’s voice is small, yet the objectification of women in Othello is impossible to ignore through her. She reveals society’s casual cruelty, showing that being female and lower-class is double jeopardy.

While the tragedy centers on Desdemona and Othello, Bianca’s marginalised perspective reminds us that injustice in Shakespeare’s Venice hits differently depending on where you stand in the social hierarchy.

Male Attitudes Towards Women in Othello

When I teach this play, I tell my students to watch the men closely. The tragedy of Othello is powered by warped male attitudes- how relationships between men and women in Othello are shaped by insecurity, suspicion, and a dangerous need to control.

i) Othello’s Insecurity:

Here’s a live classroom moment: I pause and ask, “Does Othello doubt Desdemona, or himself?” Silence. Then the penny drops. Othello’s love is real, but his confidence isn’t. As an outsider, he carries an invisible crack in his identity, and Iago knows exactly where to press.

When Othello says, “Haply, for I am black,” we hear insecurity speaking louder than reason. His attitude toward Desdemona shifts, from partner to proof. Instead of trusting love, he starts auditing it, like a nervous accountant checking for fraud. And insecurity, once invited in, never comes alone.

ii) Iago’s Misogyny:

If Othello is tragically insecure, Iago is proudly poisonous. I often tell my students: Iago doesn’t just hate people. He systemically underestimates women. His lines drip with contempt, reducing women to appetites and appearances. “You are pictures out of doors, bells in your parlours,” he sneers, turning women into decorative objects.

This misogyny isn’t background noise. It’s fuel. By normalising suspicion and sexual slander, Iago creates a world where distrusting women feels logical, even masculine. He teaches the men how to think, and once that lesson lands, tragedy follows like a bad echo.

iii) How Mistrust Leads to Violence:

This is the moment when I lower my voice in class. Because mistrust in Othello doesn’t stay verbal. It turns physical. Once women are seen as deceptive, controlling them feels justified.

Othello convinces himself that killing Desdemona is an act of justice, not murder: “Yet she must die, else she’ll betray more men.” That line always chills the room.

Violence becomes “necessary” when empathy is replaced by fear. Shakespeare shows us something uncomfortable here: when mistrust governs relationships between men and women, love curdles into cruelty, and the cost is irreversible.

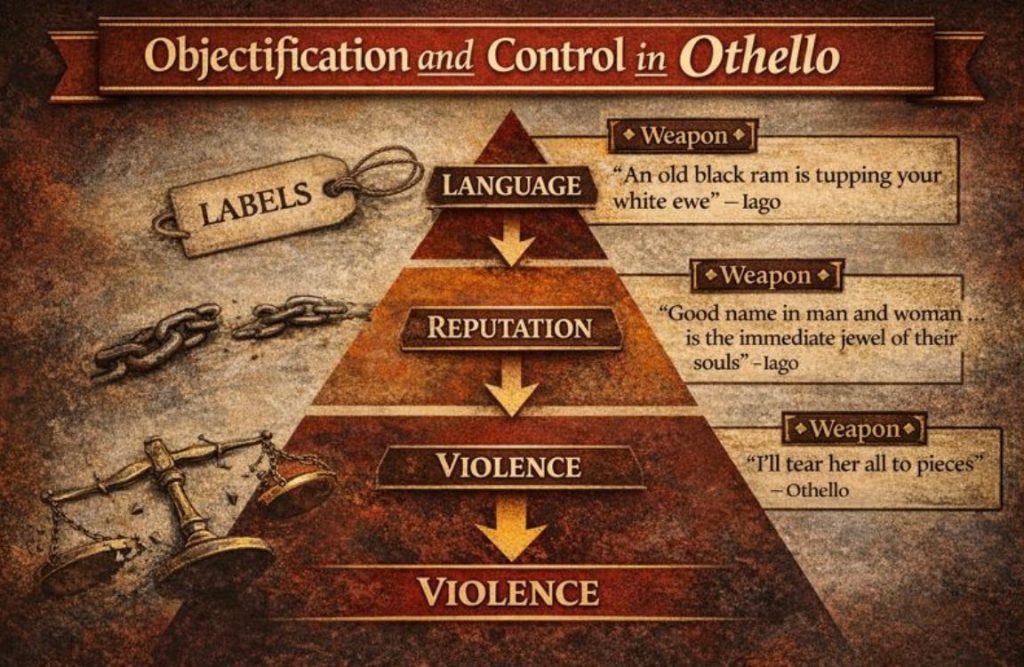

Objectification, Misogyny, and Control:

When I guide my students through this section, I warn them: this is where words become weapons. The objectification of women in Othello and its patriarchal value system reveal how language, reputation, and blame are used to control female lives.

i) Language Used About Women:

Here’s a live classroom trick I use: I ask students to circle every time a woman is described like a thing. The page fills up fast. Iago calls women “pictures,” “players,” and “wildcats”, not people, but objects with labels.

Even Desdemona, the most virtuous character, is reduced to a body that can supposedly “err.” When Othello refers to her as a “lewd minx,” I pause and ask, “Where did the woman go?” That’s the danger. Once language strips away humanity, cruelty no longer feels cruel. It feels reasonable.

ii) Sexual Reputation as Power:

I tell my students that in Othello, reputation is currency, and women are always poorer. A man’s honour can wobble and recover; a woman’s chastity, once questioned, is treated as permanently damaged.

Desdemona doesn’t need to commit adultery. She only needs to be suspected. Iago understands this terrifying imbalance perfectly. He never proves anything. He merely suggests. And suggestion is enough.

Sexual reputation becomes a leash, tightening with every whisper. Shakespeare exposes how patriarchal societies turn women’s bodies into battlegrounds, where truth matters far less than male anxiety.

iii) Women Blamed, Men Excused:

This is where my classroom usually goes quiet. Desdemona is murdered, yet Othello is pitied. Emilia speaks the truth, yet pays with her life. I ask my students, “Who actually causes the damage here?”

The answer is uncomfortable. Men’s jealousy is excused as passion. Women’s silence is treated as guilt. Othello frames his violence as moral duty: “She must die, else she’ll betray more men.”

That line exposes the final cruelty: women are blamed not for what they do, but for what men fear they might do. And Shakespeare makes sure we feel the injustice burn.

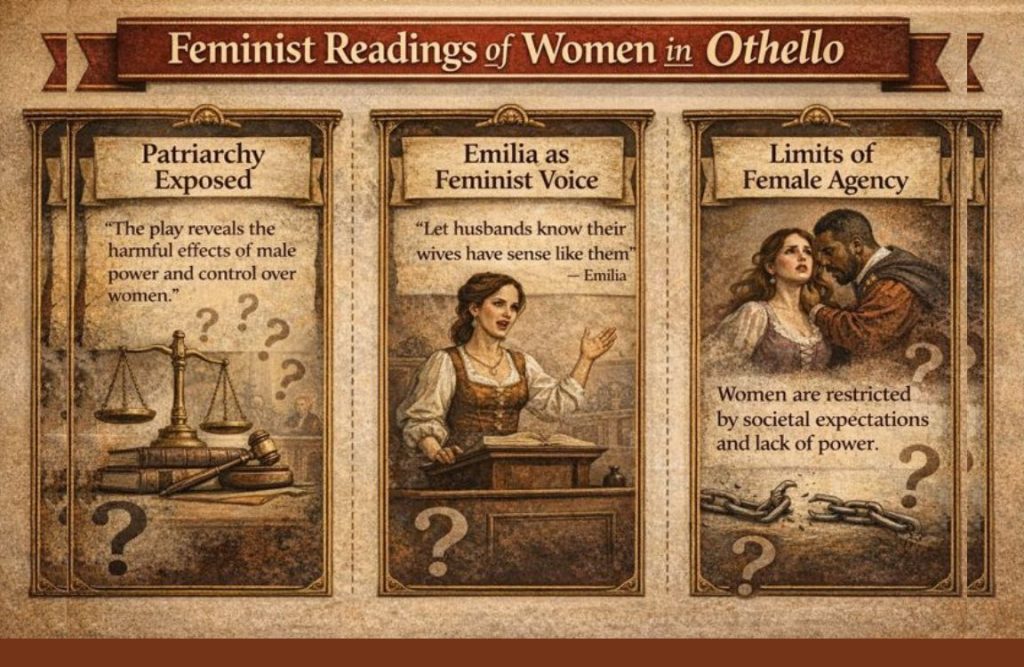

Feminist Readings of Women in Othello

When students ask me how Shakespeare presents women in Othello, I smile and say: he doesn’t hand us answers. He hands us pressure points. Read through a feminist lens, the play starts arguing back at its own patriarchy.

i) Is Shakespeare Critiquing Patriarchy?

Here’s my favourite live teaching move: I ask, “Is Shakespeare endorsing sexism, or staging it so we can’t ignore it?”

Watch what happens. The women suffer, yes, but the system that crushes them also collapses. Fathers lose daughters. Husbands lose reason. Power eats itself.

Shakespeare lets patriarchy speak loudly, and then shows its consequences. That’s not approval. That’s exposure. The men who claim authority end in chaos, while the women who are silenced are proven right too late.

The play feels less like a celebration of male control and more like a courtroom where patriarchy is cross-examined and found guilty.

ii) Emilia as a Proto-Feminist Voice:

Every year, Emilia steals the lesson. I pause the class before her speech and say, “Listen, this sounds modern.” Then she delivers it: “Let husbands know / Their wives have sense like them.” Boom.

That line lands like a dropped microphone. Emilia challenges double standards, sexual hypocrisy, and male entitlement in one breath. These are some of the strongest feminist quotes in Othello, and they don’t whisper. They argue.

Emilia doesn’t ask for equality politely. She reasons it. She imagines women as thinking, desiring humans, not moral decorations. In that moment, Shakespeare lets a woman say what the play itself has been circling all along.

iii) Limits of Female Agency:

And yet, this is where I slow down and let the discomfort sit. Emilia speaks, Desdemona loves, Bianca feels… and still, they all lose. Feminist readings must wrestle with this contradiction.

Shakespeare gives women insight, but not power. Their voices arrive late, their truths unheard, their bodies unprotected. I tell my students: agency exists here, but it’s rationed.

Women can see clearly, but they can’t steer events. That limitation isn’t a flaw in the reading. It’s the point. The play exposes a world where women understand injustice long before they are allowed to escape it.

Key Quotes About Women in Othello

When revision panic hits, I tell my students this: quotes are your evidence, but interpretation is your power. These key quotes about women in Othello, read through a feminist lens, aren’t just lines to memorise. They’re pressure points where Shakespeare exposes fear, control, and injustice.

Quote 1: “She never yet was foolish that was fair.”- Othello

I pause here and ask my class, “Compliment or warning?” Othello’s praise is conditional. Desdemona’s worth is tied to beauty and perceived intelligence, but only as long as it reassures him.

The moment suspicion creeps in, this admiration curdles. Shakespeare shows how quickly idealisation turns into ownership when women are valued for traits men want to control.

Quote 2: “I am black / And have not those soft parts of conversation / That chamberers have.”- Othello

Although spoken about himself, this quote explains how Othello views Desdemona. I tell students: insecurity rewrites love. Othello believes he must lose her because other men are “smoother.”

Women become prizes men compete for, not partners they trust. Shakespeare links male self-doubt to the suspicion of female faithfulness.

Quote 3: “You are pictures out of doors, bells in your parlours.”- Iago

This line always earns groans in class, and rightly so. Iago reduces women to decorations: pretty, noisy, and empty. It’s a verbal stripping of humanity.

Shakespeare lets misogyny speak plainly here, without disguise. The bluntness matters. We are meant to hear how casual cruelty sounds when it’s socially accepted.

Quote 4: “Let husbands know / Their wives have sense like them.”- Emilia

Every year, this line wakes the room up. Emilia refuses silence. I tell my students this is one of the boldest moments in the play, logic weaponised against hypocrisy.

Emilia argues that women think, feel, and desire just like men. Shakespeare places this truth in a woman’s mouth, daring the audience to disagree.

Quote 5: “O, these men, these men!”- Desdemona

This line is heartbreakingly quiet. Desdemona doesn’t accuse. She sighs. I ask my class, “Is this innocence or awareness?” It’s both.

She senses injustice but lacks the power to confront it. Shakespeare captures how women often recognise oppression long before they are able to resist it.

Quote 6: “She must die, else she’ll betray more men.”- Othello

This is the line I lower my voice for. Othello reframes murder as morality. I remind students: when fear replaces empathy, violence feels justified.

Desdemona is punished not for actions, but for imagined possibilities. Shakespeare exposes the terrifying logic of control, where women are destroyed to protect male honour.

FAQs:

Why are women powerless in Othello?

When I ask this in class, students say, “Because men rule.” True, but incomplete. Women lack legal, social, and narrative authority. They speak insightfully, yet too late. Power in Othello belongs to those believed first, not those who are right.

Is Othelloa feminist play?

I tell my students it’s not feminist propaganda, but it’s feminist-friendly. Shakespeare exposes injustice without fixing it. He stages patriarchy, lets it self-destruct, and leaves us unsettled. That discomfort is the point, and a very modern one.

Who suffers most among the women in Othello?

Desdemona dies quietly, Emilia dies loudly, and Bianca survives shamed. In class, we debate this fiercely. I argue Desdemona suffers most physically, Emilia morally, and Bianca socially. Shakespeare distributes suffering unevenly, just like real life.

How many women are in Othello?

Only three- Desdemona, Emilia, and Bianca. I joke with students: “Small cast, heavy consequences.” Each woman represents a different social position, allowing Shakespeare to explore gender across class, marriage, and morality in a tightly controlled space.

Is Emilia a feminist in Othello?

I say she’s not carrying a manifesto, but she’s carrying a mic. Emilia questions double standards, male entitlement, and silence. Her ideas sound centuries ahead of her world, which makes her bravery and her fate even more powerful.

How is Bianca presented in Othello?

Bianca is introduced through judgment, not sympathy. I ask students to notice how others describe her before she speaks. She’s framed as disposable and emotional, yet Shakespeare gives her genuine feelings, challenging the stereotype as he exposes it.

How is Bianca a victim in Othello?

Bianca survives, but survival isn’t victory. She’s mocked, suspected, and discarded. I remind my class: tragedy doesn’t always kill. It sometimes humiliates. Bianca pays for male actions with her reputation, proving how cruelty extends beyond the final act.

Final Analysis:

When I close this lesson, I tell my students that the real tragedy of Othello isn’t just jealousy. It’s moral blindness. A careful analysis of women in Othello shows that the women carry the play’s ethical truth. They love honestly, speak clearly, and suffer disproportionately.

Desdemona exposes the cost of misplaced trust, Emilia exposes the danger of silence, and Bianca exposes how easily society discards women it doesn’t respect.

Together, their stories shape the women’s experience in Othello, revealing Shakespeare’s representation of women as moral mirrors, reflecting what the men refuse to see. Their suffering matters because it isn’t accidental; it’s structural.

Shakespeare forces us to watch what happens when power listens to fear instead of empathy. And that’s why this play still unsettles us today. It keeps whispering into modern debates about gender, voice, and whose truth gets believed first.